|

| Fox Cottage at Lily Dale NY |

Almost done with the revisions to my introduction to my translation of Francisco I. Madero's secret book of 1911, Spiritist Manual (for those of you who are new to the blog, Madero was the leader of Mexico's 1910 Revolution and President of Mexico from 1911-1913).

***UPDATE my book, Metaphysical Odyssey Into the Mexican Revolution, is now available***

Meanwhile, apropos of that, I found this circa 1950s postcard on ebay...

"FOX COTTAGE, LILY DALE, N.Y."Memorial to the Fox Family who lived in this cottage at the time Margaret [sic] and Katie Fox aged 9 and 11 years received the first proof of the continuity of life which was the beginning of modern spiritualism, March 31, 1848. This cottage was bought and moved from Hydesville, N.Y., its original site, to Lily Dale, N.Y., in May 1916 by Benjamin F. Bartlett.

Lily Dale is the Mecca of Spiritualism. Visit the Lily Dale Assembly website here. Learn more about the history in Christine Wicker's excellent odyssey, Lily Dale: The Town That Talks to the Dead.

Here's an excerpt from my introduction to Madero's Spiritist Manual of 1911, a bit about the Fox sisters and their haunted house:

The Foxes, a Methodist farmworker family, the father a blacksmith, moved into their cottage shortly before Christmas of 1847. There would have been snow pillowing up to the windowsills, and a pre-electric sky spectacular with stars. On their straw-stuffed mattresses, the family would have been bundled in blankets and quilts. But through the cruel winter nights of 1848, their sleep suffered with odd noises, crackles, scrapings—as if of moving furniture; and bangs and knocks. By springtime the children had become so frightened by the “spirit raps,” they insisted on sleeping with their parents. As Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (yes, of Sherlock Holmes fame) recounts in The History of Spiritualism:

Finally, upon the night of March 31 there was a very loud and continued outbreak of inexplicable sounds. It was on this night that one of the great points of psychic evolution was reached, for it was then that young Kate Fox challenged the unseen power to repeat the snaps of her fingers. That rude room, with its earnest, expectant, half-clad occupants with eager upturned faces, its circle of candlelight, and its heavy shadows lurking in the corners, might well be made the subject of a great historical painting. Search all the palaces and chancelleries of 1848, and where will you find a chamber which has made its place in history as secure as this bedroom of a shack? The child’s challenge, though given in flippant words, was instantly answered. Every snap was echoed by a knock. However humble the operator at either end, the spiritual telegraph was at last working.

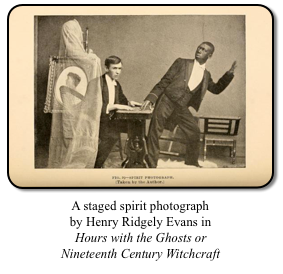

Kate Fox, eleven, and her sister, Maggie, fourteen, determined that the spirit they called “Mr Split-foot” was that of a peddler who had been murdered and buried in the house. Conan Doyle, who went so far as to reprint the sworn April 11, 1848 testimony of both parents, was one of many Spiritualists, as they came to call themselves, who considered the events in the so-called “Spook House” of Hydesville “the most important thing that America has given to the commonweal of the world.” And whether one laughingly discards, ardently accepts, or would finely sift and resift ad infinitum the evidence of the existence of said murdered peddler and any communications from beyond the veil, the fact is that whatever it was that happened in Hydesville ignited an enthusiasm for “spirit” phenomena evoked in the ritual of the séance from channeling to table tipping to pencils and chalk stubs writing by themselves, or by means of a planchette; clairvoyance; flashes of light and floating orbs; levitation; ectoplasmic hands, feet and faces oozing out of velvety darkness; and “spirit photography” throughout the Burned-Over District, north to Canada, out west, south, to England and Ireland and, at full-gallop, across the European continent into Russia.

Meanwhile, the Fox sisters received an avalanche of press, especially after P.T. Barnum put them on display in his American Museum on New York City’s Broadway, charging a dollar— then more than a tidy sum— to communicate through them to the ghost of one’s choice. (As science historian Deborah Blum recounts in Ghost Hunters, among those who paid their dollar were the novelist James Fenimore Cooper and Horace Greely, editor of The New York Tribune, both of whom left convinced that they had heard from spirit.) Scores of mediums now emerged, claiming to communicate with spirits as diverse as a drowned child, Egyptian high priests and “astral” beings; seeking them out in darkened rooms came legions of the bereaved, curiosity-seekers, skeptics on a mission, and not a few intellectuals (among them, novelist Victor Hugo, chemist Sir William Crookes, and naturalist Alfred Russell Wallace—more about them in a moment).

Among the celebrated mediums in this period were the English Florence Cook; Nettie Colburn, who gave séances for Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln in the White House; and Scottish-born American Daniel Dunglas (D.D.) Home, who toured France in the 1850s, which, according to historian John Warne Monroe, “seemed to mark the first step in the spread of this second, metaphysical American Revolution.” Home’s séances, like his audience itself, had attained a new level of glamour, a world apart from the Fox sisters. Attended by royalty, including the Emperor Louis Napoleon and his Empress Eugénie, and high society of all stripes, according to Janet Oppenheim in The Other World, an evening with Homes might feature a spine-tingling cornucopia of phenomena:

. . . furniture trembled, swayed, and rose from the floor (often without disturbing objects on its surface); diverse articles soared through the air; the séance room itself might appear to shake with quivering vibrations; raps announced the arrival of the communicating spirits; spirit arms and hands emerged, occasionally to write messages or distribute favors to the sitters; musical instruments, particularly Home’s celebrated accordion, produced their own music; spirit voices uttered their pronouncements; spirit lights twinkled, and cool breezes chilled the sitters. If Home announced his own levitation, as he did from time to time, the sitters might feel their hair ruffled by the soles of his feet.

But before we segue to Paris of a few decades hence, where we will encounter our Mexican author of destiny, then with a full head of hair, let us float down from the ceiling for a moment, back to the grittier question of roots. . . .

+++

More excerpts:

> Your comments are always welcome. Write to me here.

Strange as it may sound, a vital taproot of the Mexican Revolution lies in Upstate New York. Read all about it in my guest blog for the New York History Blog-- an excerpt from my latest book, Metaphysical Odyssey into the Mexican Revolution.

Strange as it may sound, a vital taproot of the Mexican Revolution lies in Upstate New York. Read all about it in my guest blog for the New York History Blog-- an excerpt from my latest book, Metaphysical Odyssey into the Mexican Revolution.